Academic phrases

What phrases can I delete or shorten to make my writing more concise?

Make your academic writing more concise with these replacements:

- due to the fact that = because

- based on the fact that = since, as, because

- on account of the fact that = because, as

- in an effort to = to

- with regard/respect to = concerning, regarding

- point in time = moment

- at the present time = currently

- in spite of the fact that = although

- in order to = to

- in reference to = regarding

- in the vicinity of = near

- on a daily basis = daily

- on the subject of = about

- with the exception of = except for

- to conduct an investigation into = to investigate

- to give an indication of = to indicate

- to make a plan = to plan

- to make a decision = to decide

- to draw a conclusion = to conclude

- to collaborate together = to collaborate

- to connect, join together = to connect, join

- comparatively smaller than = smaller than

- equally as good = equally good, equal

- future prospects = prospects

- the color yellow = yellow

- shorter in length = shorter

Use Writefull’s language check, tailored to research writing, to make sure your text is as concise as possible.

What’s a common way to start a sentence in academic writing?

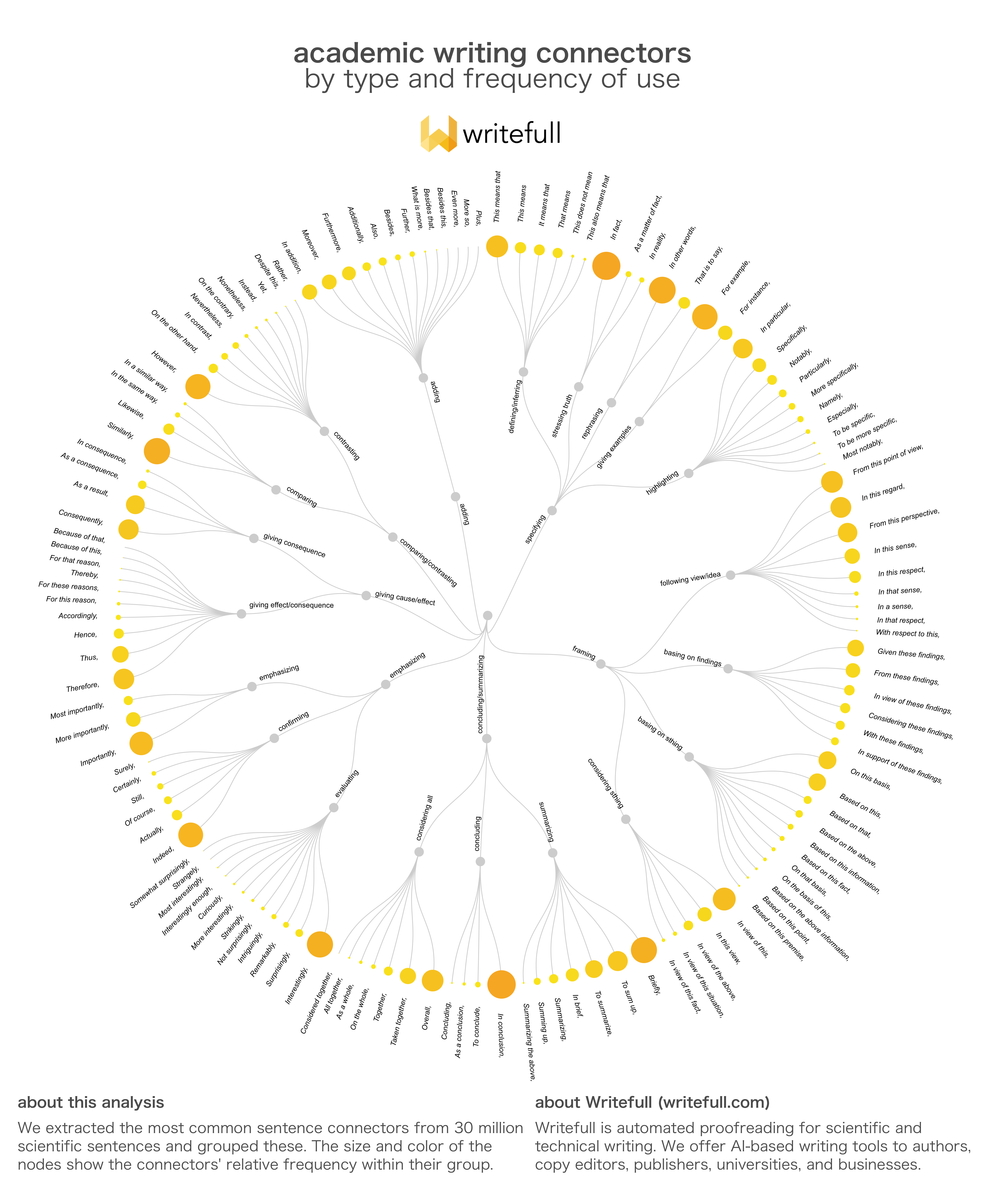

In many cases, sentences will start with a word or phrase that links to the previous sentence. These are called ‘connectors’ or ‘transition words’. At Writefull, we’ve analyzed published papers to see how authors usually start their sentences in academic writing. You can find the results here.

We found that the three most-used linking words were ‘however’, to present contrasting information, and ‘therefore’ and ‘thus’ to present a result or effect. At the phrase level, authors often started their sentences by introducing a study, section, or data. For example: ‘This study explored …’, ‘The aim of this study …’, ‘In this section, …’, ‘Table 2 shows,’ and ‘As can be seen in Figure 1, …’

Check Writefull’s Sentence Palette for over 600 useful phrases and words to start your sentences with.

What words can I use to connect or bridge two sentences?

How you link two sentences depends on their relationship: Does the second sentence give examples, add information, contrast, or do something else? Our analysis of published papers shows you what connectors authors use most, depending on the sentence goal. We found that these are the top sentence connectors of seven common goals:

- To add information: In addition, Moreover, Furthermore, Additionally, Also,

- To specify: This means that, In fact, In other words, For example/instance, In particular, Specifically, Notably, Particularly,

- To frame, give context: From this point of view, From this perspective, In this regard, Given these findings, On this basis, Based on this, In view of this,

- To summarize, conclude: Briefly, To sum up, To summarize, In conclusion, Overall,

- To emphasize: Interestingly, Surprisingly, Indeed, Importantly, More importantly,

- To express cause and effect: Therefore, Thus, Consequently, As a result,

- To compare and contrast: Similarly, Likewise, However, On the other hand,

How do I compare and contrast two things in my paper?

You can compare and contrast in different ways. The first is to bridge two sentences with a connector that shows how two things are similar or different. For example: ‘Smith used approach A. In contrast, Berkmans used approach B. ‘

These are the most common compare/contrast connectors used in research writing:

- To compare: Similarly, Likewise, In the same way, In a similar way,

- To contrast: However, On the other hand, In contrast, Nevertheless, On the contrary, Nonetheless, Instead, Yet, Despite this, Rather,

You can also mention the linking word within a sentence, instead of at the start of a sentence. With the phrase ‘in contrast’, this could look like this: **‘Smith used approach A. Berkmans, in contrast, used approach B.’

Besides using connectors, you can use one of the following sentence structures to indicate a comparison or contrast:

To compare:

- Smith and Berkmans both used approach A.

- Smith, like Berkmans, used approach A.

- Approach A, used by Smith, was also used by Berkmans.

- Approach A was used by (both) Smith and Berkmans.

- The same approach was used by Smith and Berkmans, namely, approach A.

To contrast:

- Smith used approach A; however, Berkmans used approach B.

- While Smith used approach A, Berkmans used approach B.

- Smith and Berkmans used approach A and B, respectively.

- Smith and Berkmans used a different approach: Smith used A, Bermans used B.

- The approaches used were A by Smith and B by Berkmans.

For more phrases to compare and contrast, browse Writefull’s Sentence Palette.

How do I highlight a gap in the research field?

Highlighting a gap in the field is something you’ll typically do in your Introduction, where you give context and explain why your paper is relevant.

Common phrases to highlight a gap in the research field:

- Few studies have explored / considered …

- Studies on this topic have overlooked …

- There is little knowledge of …

- Research has been limited to / focused mainly on …

- It remains unclear if / to what extent …

Example sentences highlighting a gap in the research field:

- As research has mainly focused on the immediate learning effects, the current study measures long-term retention with a delayed post-test.

- Few studies have explored the practical applications of Exec-F10 in countries other than Poland.

- It remains unclear whether this form of therapy reduces pain.

For more phrases to highlight a gap in your field, browse Writefull’s Sentence Palette.

How do I write what future research should focus on?

In your Discussion or Conclusion, you’ll typically state what should be addressed in future research. This is often a question that your study raises, or has failed to address.

Common phrases to refer to future research:

- Future research should explore / investigate / consider / address …

- More studies should aim to / concentrate on …

- Additional studies are needed to …

- Further data collection would help to gain insights into …

- Further analysis is needed to …

- A key area to be explored further is …

- An important issue / problem / question to address is …

Example sentences referring to future research:

- Considering the small subject pool of this study, further analysis is needed to investigate whether these numbers are representative.

- A key area to be explored further is redistribution, which has received little attention in this market segment.

- Future research should shed more light on how increased mobility affects the performance of sales representatives.

For more phrases to refer to future research, browse Writefull’s Sentence Palette.

Also see a few examples of authors discussing future research.

How do I concisely and clearly summarize my results?

In your Discussion, you’ll want to summarize your key findings in a few sentences. In your Abstract, you’ll typically devote only one or two sentences to your results. This means it’s important to be brief and clear.

Common phrases to summarize your results:

- This study found a relationship / association between …

- The data reveal / indicate / suggest …

- This paper has shown / provided / described / identified …

- The results did not show evidence of / confirm …

- It was observed / found / shown that …

Example sentences summarizing results:

- This work found a direct relationship between primary language disorders and screen exposure among toddlers.

- This study investigated the effect of gender on employees' perception of job satisfaction, and found no significant differences.

- The data indicate that small increases in the level of light lead to sleep disruption in preterm infants.

For more phrases to summarize your results, browse Writefull’s Sentence Palette.

How do I discuss the limitations of a study without sounding negative or harsh?

It’s important to show critical thinking in your research paper or thesis, and when discussing the existing literature. But be careful not to sound arrogant or negative. Make sure to avoid adjectives such as ‘weak’ or ‘disappointing’ when writing about others’ work, and to present limitations using neutral wording.

Common phrases to discuss the limitations of other studies:

- A limitation of Smith’s study is …

- The study did not take into account …

- One can question the validity of these conclusions, as …

- While a rigorous study, the findings presented by Smith are limited to…

- As Smith’s subject pool included nurses only, it remains unclear whether …

Example sentences discussing limitations:

- A limitation of the authors’ study is that it considered only the emotional exhaustion dimension of burnouts, which is known to be one of the first phases.

- Smith’s findings are based on a participant pool of primarily hospital employees, who are more likely to develop these symptoms.

- While Smith’s predictions would indeed show limited effects, one can question the validity of the model underlying these predictions.

For more phrases to discuss limitations of studies, browse Writefull’s Sentence Palette.

Should I use ‘need not’ or ‘does not need to’ in academic writing?

You can use both. They mean the same thing, but the second is more common, including in academic writing. The former (‘need not’) may feel a bit archaic, but is also perfectly fine to use. Note that ‘need not’ is always followed by an infinitive; for example, ‘need not be’ or ‘need not include’.

A few example sentences of the two:

- This need not be tied to the scale used. This does not need to be tied to the scale used.

- Models that contribute to VVHN need not specify the dimensions.Models that contribute to VVHN do not need to specify the dimensions.

- Griffith’s theory need not rule out the possibility of differences.Griffith’s theory does not need to rule out the possibility of differences.

Want to explore how certain words and phrases are used in published papers? Use Writefull’s Language Search.

Should I use ‘has got’ or ‘has gotten’ in academic writing?

Which one you should use depends on the English variety you’re following: UK or US English.

‘Has got’ is the present perfect tense of the verb ‘to get’ in UK English. For example: ‘The subject gets an invitation.’ > ‘The subject got an invitation.’ > ‘The subject has got an invitation.’

‘Has gotten’ is the present perfect tense of the verb ‘to get’ in US English: ‘The subject has gotten an invitation’.

In US English, ‘has got’ is used too, but in ways that are too informal for academic writing, namely:

- as the present tense of ‘to have’. An example would be ‘This study has got several limitations’, but in an academic text, you would write ‘This study has several limitations’.

- to mean ‘must’; for example, ‘This value has got to be multiplied.’ In an academic text, it would be more appropriate to write: ‘This value must be multiplied.’

Use Writefull’s automated language check to make sure your language isn’t too informal for academic writing, and Writefull’s Language Search to see how to use certain words or phrases.

How should I use ‘either … or’ in academic writing?

You can use ‘either/or’ in academic writing to emphasize that one of two options can apply. In informal language, especially in speech, ‘either/or’ is sometimes used with more than two options too; for example, ‘Participants could either swim, run, or walk.’ However, strictly speaking, ‘either/or’ is used when there are two options only, so for academic writing, it is best to stick to this too.

This means that you can write:

- ‘Participants could swim or run’ (they could do one of the two, possibly both - this isn’t clear), or

- ‘Participants could either swim or run’ (they could do only one of the two - if one applies, the other does not)

To keep your ‘either/or’ easy to read, keep them close to each other and to the elements they refer to. For example, instead of writing ‘either applying A or B’, write ‘applying either A or B’.

For more insights into how to use phrases, use Writefull’s Language Search.

How should I use ‘both … and’ in academic writing?

‘Both/and’ can be used to emphasize that two things or people apply. If you don’t want this emphasis, use ‘and’ only. ‘Both/and’ is fine to use in academic writing; it is not informal, nor is it very formal.

Compare:

- Students completed an immediate and delayed post-test.

- Students completed both an immediate and delayed post-test.

The second sentence emphasizes that all students took both tests.

‘Both/and’ is always followed by a plural verb form, even if the two elements are singular. For example, ‘Both the immediate and delayed post-test cover (and not ‘covers’) 20 questions.’.

To keep your ‘both/and’ clear, make sure there isn’t too much distance between the two, nor between the elements they refer to. For instance, instead of writing ‘both the peaks of A and B’, write ‘the peaks of both A and B.’

Writefull’s Language Search shows you how phrases like these are used in academic papers, and lets you compare variations to see what’s the best way of writing something.

Can I use expressions like ‘of course’ and ‘needless to say’ in academic writing?

Whether or not such expressions are acceptable depends on the discipline, the type of publication, and most of all, the reader. In general, the arts and humanities and some social sciences allow more space for such expressions than the natural sciences do. In terms of publication types, you are more likely to find them being used in letters to the editor or book reviews than in research articles.

In research articles, you want to be objective and neutral. Using expressions like ‘of course’ and ‘needless to say’ are not in line with this, as they suggest your findings or interpretations are obvious - and maybe they aren’t to the reader.

Consider removing ‘needless to say’ and ‘of course’. Here are some alternatives to the sentence ‘Needless to say, eating fruit is healthier than eating chocolate.’:

- It is well-known that eating fruit is healthier than eating chocolate.

- As (widely) known, eating fruit is healthier than eating chocolate.

- Eating fruit is healthier than eating chocolate.

- Many studies [add references] have shown that eating fruit is healthier than eating chocolate.

Download Writefull to get feedback on your text, and to ensure it sounds academic and neutral!

What should I use in academic writing: ‘regarding’, ‘with regard to’, ‘with regards to’, ‘in regards with’, or ‘in regards to’?

First, in any type of writing, avoid the phrases ‘with regards to’, ‘in regards with’, and ‘in regards to’. Some of those are used, but they are incorrect. Instead, use ‘in regard to’ or, more commonly, ‘with regard to’.

You can also use ‘regarding’; if the above forms are confusing, it might be safe to stick to that instead.

All forms mean ‘concerning’ or ‘about’.

For example:

- This study explores physician attitudes in regard to patient interaction.

- This study explores physician attitudes with regard to patient interaction.

- This study explores physician attitudes regarding patient interaction.

- This study explores physician attitudes concerning patient interaction.

Use Writefull’s language check on your research texts to make sure you don’t make mistakes with phrases like these.

Should I write ‘the table/figure below’ or ‘the below table/figure’?

While you sometimes see the words ‘below’ or ‘above’ positioned after the noun, the correct way is to place them before it: ‘the table below’ or ‘the figure below’. This is because the word ‘below’ does not describe the table or figure; it only states where they are positioned (just like you would say ‘the house there’ and not ‘the there house’).

Another tip: For clarity, it’s best not avoid words and phrases like ‘above’, ‘below’, ‘here’, ‘next’, ‘in the next section’, ‘in the paragraph above’ or ‘on the previous page’. This is because online publications lack the spatial properties that physical journals and books have. The text, tables, and figures can be positioned anywhere once published - and what is above or below in your document may be elsewhere for the reader. So instead, refer to the table or figure number or, where relevant, to the section number. For example, instead of ‘the table below shows’, write ‘Table 5 shows’, and instead of ‘the next section’, write ‘Section 3.1’.

Use Writefull’s Language Search to directly compare which of two phrases is most frequently used in published papers.

Should I write ‘data is’ or ‘data are’ in academic writing?

In most cases, it’s best to use ‘data are’. And here’s why.

The word ‘data’ is often used as a mass noun, like ‘information’ or ‘research’. Similarly to these, it is thought as an uncountable whole rather than a combination of multiple elements. For this reason, ‘data is’ is more common than ‘data are’, especially in spoken language.

However, many people consider ‘data is’ incorrect. This comes from the fact that in Latin, ‘data’ is the plural form of the word ‘datum’; and based on this, ‘data’ should be followed by a plural verb form (‘data are’).

In academic writing, where language accuracy is key, it is safest to go with ‘data are’, and follow the Latin-derived grammar rule.

A few examples:

- The survey response data were collected in May, 2021.

- The data in Table 4 show an increase over time.

- The data were entered by a lab assistant.

There is an exception to this rule: If you’re referring to an amount of data, in terms of size or storage, the singular form is used. For example: ‘The video data makes up 10GB.’

Writefull’s language check will ensure you don’t make mistakes with tricky works like these, and its Language Search lets you compare frequencies of different word combinations.

Can I write ‘the reason is because’ in academic writing?

Although ‘the reason is because’ has been used in the literature for centuries, there has been discussion about whether or not it is grammatically correct. There clearly is redundancy in the phrase, as ‘the reason is’ already indicates ‘because’. This is why many consider the phrase awkward or even incorrect.

While the phrase is common in conversation, you may want to avoid it in academic writing, and use ‘The reason is that’ or ‘because’ instead. For example: ‘These numbers are not reliable, because data points are missing.’

To make sure you avoid awkward or lengthy phrases in your own paper or thesis, use Writefull’s free language check.

What’s a shorter version of ‘It should be taken into account that’?

‘It should be taken into account that’ is fine grammatically, but a bit lengthy. It can be shortened with a simple ‘Note that’. For example: ‘Note that these effects may disappear over time.’

Other constructions to use instead of ‘It should be taken into account that’ are:

- It should be noted that

- It should be mentioned that

- It should be considered that

- One should bear in mind that

Find more conciseness tips for academic writing here.

What’s a shorter version of ‘due to the fact that’ or ‘based on the fact that’?

In many cases, both phrases can be replaced by ‘because’, ‘since’, or ‘as’. Note that this might slightly change the meaning. For example:

- Production costs increased due to the fact that more apples were needed.The fact that more apples were needed directly increased production costs.

- Production costs increased because / since more apples were needed.

Like ‘due to the fact that’, ‘because’ and ‘since’ indicate that the increased costs related directly to the fact that more apples were needed.

- Production costs increased as more apples were needed.

The ‘as’ shows that the increase in apples went hand in hand with the increase in production cost. This can mean that the apples caused the increased production costs, but this isn’t explicit; maybe the two were just happening at the same time. If you add a comma after ‘increased’, there’s a stronger sense of cause and effect: ‘Production costs increased, as more apples were needed.’

What’s an alternative to ‘in conclusion’?

There are several alternatives to ‘in conclusion’, and which one is appropriate depends on your context.

- If you’re summarizing your findings:

- To summarize,

- In summary,

- In short,

- In brief,

- If you’re introducing a key statement derived from your results:

- Taking these results,

- Based on this data,

- As (has been) shown / demonstrated,

- As these results show / indicate,

- If you’re drawing a conclusion from multiple pieces of information:

- Overall,

- All in all,

- In general,

- Taking all into account,

- If you want to introduce your conclusion with caution:

- Although one should be careful with generalizing,

- While further study is warranted,

- Based on these initial results,

- This data suggests that

Use Writefull’s language check to make sure your phrases are correct and appropriate for academic writing!